The

director of the award-winning ensemble Les Arts Florissants talks about working

with vocalists on the music of the 17th and 18th centuries, and about a new

advanced training program for young artists.

William Christie has come a long way for a boy from Buffalo. After

college and graduate work at Harvard and Yale, he went to Paris for advanced

study on the harpsichord at the Conservatoire. He's never left — he was

awarded the Légion d'Honneur in 1993 and became a naturalized French citizen in

1995, and it is in France (in Paris and Caen) that Christie's renowned ensemble

Les Arts Florissants is based. Founded in 1979, this group has done

extraordinary work in bringing neglected 17th- and 18th-century works to life

for modern audiences — a range of musical riches from oratorios by

Carissimi and Handel to operas by Purcell, Mozart and Gluck. Most of all,

Christie and Les Arts Florissants have done more than anyone else to restore the

great music of the French Baroque — the operas and sacred works of

Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau and especially Marc-Antoine

Charpentier — to the repertory.

What's more, working with William Christie has

been crucial to the career track of any number of singers, including

(among many others) Véronique Gens, Mark Padmore and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. Shortly before a performance of Monteverdi's opera Il ritorno d'Ulisse in

patria (The Return of Ulysses) in Caen, andante's Matthew

Westphal spoke with Christie about what he looks for in the singers he works

with.

Matthew Westphal: How did you wind up making your way from being a

harpsichordist to being a director and teacher of singers?

William Christie: I'm not a teacher of singers, first of all — I

don't teach technique at all, I never would. I have very strong ideas about it

but I don't do it — it's very destabilizing for someone to come to me

and then be told that they've got to change techniques. That's something which

happens over a long period of time with a good teacher, a good technical teacher.

As to how a harpsichordist becomes an ensemble person ... well, that's the

nature of the instrument. It collects people around it. It always was the center

of the orchestra or the ensemble [in the Baroque era]; mostly, the people who

played harpsichord were the people who directed.

MW: Your singers — in general are most of them your

students?

WC: That's an exaggeration. In this case [The Return of Ulysses] they're young, with the

exception of the characters who need to be old. Some of them have been singing

with me in other things for a fairly long time, having come in as sort of

— I wouldn't say choir singers, but almost. We've seen already over the

last year an enormous change in some of these voices, in singers who are only 23

or 24 years old. A few are students — I think of the present cast four

or five were in my class at the Paris Conservatory; the others, of course, have

come through the Arts Florissants ensemble or through auditions.

MW: I was wondering — how do you find singers or how do they find you?

MW: I was wondering — how do you find singers or how do they find you?

WC: It's very simple: you say yes when people write

and ask for an audition — you always say yes. And then you spend a lot

of time doing it.

We do auditions every month, really. That's been even more intense over the

last six to eighth months, with auditions in Prague, Frankfurt, Paris, London,

Zurich, Madrid ... because we chose nine singers (out of several hundred) for

this new pedagogical project we're involved in called Le Jardin des Voix.

MW: Yes, I know that's starting this fall. Tell us some more about it ...

WC: The idea behind Le Jardin des Voix is special:

it's essentially taking people at the beginning of a professional career and

helping them out. That is to say, giving them the chance to sing in fabulous

halls, the best halls in Europe actually, together — in ensembles and

by themselves — in a mixed repertory of 17th- and 18th-century European

music. They'll come together in October [2002] and we'll spend several weeks

working on a program — and also working on basics with other people,

language coaches and diction coaches and style coaches and what-have-you. To

give these people who are already interested in specializing, who like "old

music" in other words, a better understanding of what they're doing —

and then to work very professionally with them on this program, which will be

accompanied by the Arts Florissants orchestra, and take them to these different

halls.

So essentially they're 20 to 30 years old, at the beginnings of careers, in a

moment that's really very critical. You've left school, the conservatory, and

you're on your own, trying to get going.

MW: Not long ago I saw an interview with Véronique Gens that said when she

was introduced to you, her voice was entirely untrained — and that was

just what you wanted, no habits.

MW: Not long ago I saw an interview with Véronique Gens that said when she

was introduced to you, her voice was entirely untrained — and that was

just what you wanted, no habits.

WC: Well, it's not really true; obviously she had

already been studying voice. I told her she should come back — I

remember vividly, she was 17 or 18 and came with her mother — I said

she should get a little more under her belt. Later she came into the [Arts

Florissants] ensemble as an ensemble singer, as a young soloist with smallish

bits. And obviously the voice began to develop and mature. She's a serious

woman, so she's always studying, and now of course she's a rather grand

lady.

MW: Is there an issue with young singers more generally — do you

find there are habits that have to be unlearned?

WC: I don't really like to unlearn things; I like to give things to people. Occasionally you'll meet very

established singers who just want to sing everything the same way. Why should I

make a effort, they'll ask me, to sound different singing Monteverdi —

well, they don't sing Monteverdi — but to sound different

singing Scarlatti or Handel from when they sing Verdi or Puccini? I don't get

many of those but I have been given a few.

Basically the whole thing is a question of curiosity, of intellectual

curiosity and intelligence and technique. If you have all three of those you can

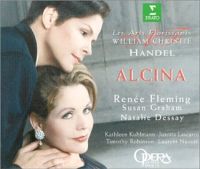

do anything you want. In particular with someone like Renée Fleming —

she can sing the most beautiful Strauss in the world, but when she comes to sing

Handel, she switches off certain priorities and she switches on others. She

listens — she's a sponge, in the most wonderful way. And since

she's got glorious technique she can do the things you ask her to do.

Basically the whole thing is a question of curiosity, of intellectual

curiosity and intelligence and technique. If you have all three of those you can

do anything you want. In particular with someone like Renée Fleming —

she can sing the most beautiful Strauss in the world, but when she comes to sing

Handel, she switches off certain priorities and she switches on others. She

listens — she's a sponge, in the most wonderful way. And since

she's got glorious technique she can do the things you ask her to do.

MW: I saw in another recent interview with you that you have "pipe dreams"

— you get all excited, for example, about Weber's Der

Freischütz. Do you think you'll be moving at all in that

direction?

WC: Oh, I have pipe dreams, but I'm much more

cautious than a number of my colleagues, I think. First of all, I'm extremely

content with two centuries that are extraordinarily rich. Some of my colleagues

seem to think that somehow you cut your teeth in the Baroque and then go on to

bigger and better things. That's nonsense. I could spend five lives and never

get through the things I want to get through in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Also, when you're talking about later repertory — that is to say,

post-Rameau or post-Bach — well, that is the 18th century and

there is an extraordinary continuity, despite the change in styles. I like to

think of Mozart and Haydn and quite a bit of Beethoven as belonging to the 18th

century. It seems to me much more interesting to approach Mozart as someone who

comes just before late Haydn or Beethoven than to sort of come back to him

tramping through an awful lot of Romantic and post-Romantic and contemporary

music.

If you would like to respond to this

interview, please write to letters@andante.com.

MW: I was wondering — how do you find singers or how do they find you?

MW: I was wondering — how do you find singers or how do they find you?

MW: Not long ago I saw an interview with Véronique Gens that said when she

was introduced to you, her voice was entirely untrained — and that was

just what you wanted, no habits.

MW: Not long ago I saw an interview with Véronique Gens that said when she

was introduced to you, her voice was entirely untrained — and that was

just what you wanted, no habits. Basically the whole thing is a question of curiosity, of intellectual

curiosity and intelligence and technique. If you have all three of those you can

do anything you want. In particular with someone like

Basically the whole thing is a question of curiosity, of intellectual

curiosity and intelligence and technique. If you have all three of those you can

do anything you want. In particular with someone like